I am not an American Express cardholder in Lakewood, New Jersey. I am not hunting for jobs in Baltimore. I am not trying to set my recovery address for gmail. And heaven knows I’m not looking for gay love in Malaysia (not any more, anyway).

I created a gmail account pretty early on—in April 2004, as best as I can tell, at a time when joining was still contingent on tapping the slow stream of invitations that were trickling out of Google HQ. As a result, I was able to get a fairly canonical user name: azriel. To be clear, this wasn’t an arbitrary choice (and no, I’m not especially fond of The Smurfs): Azriel (עַזְרִיאֵל) is simply the Hebrew name I was given as a baby. Given that I went to Hebrew school, I was even called Azriel for a time, in a limited context.

The trouble with having such a simple email address is that I end up receiving a disproportionate amount of email intended for other people. Perhaps a sender forgets to type the full azriel1984, or azriel.lastname, or whatever, and sends their message to me by accident. Over the years I’ve received other people’s tax returns, flight itineraries, death notices, real estate tips, hair appointments, and so on. Gmail’s spam filter doesn’t catch these messages, because of course they’re not spam. They’re a whole other class of insidious message: wrong-number emails. These messages don’t bear any of the obvious computational markers of spam, and even gmail isn’t smart enough to figure out that I couldn’t possibly be interested in their contents.

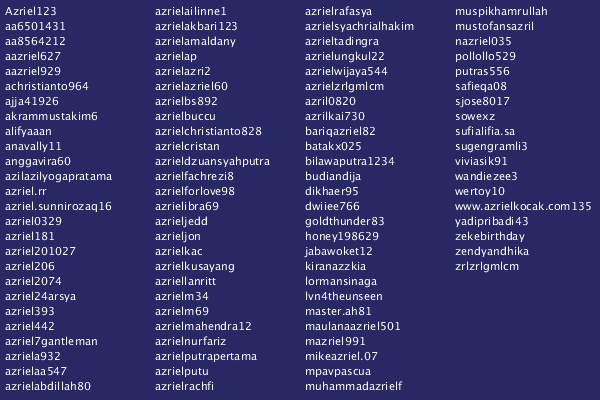

But the bigger problem is that people frequently sign up for online services using my email address instead of their own. I can’t say exactly why this happens. The most obvious explanation is that people mistype or misremember their own addresses when signing up for services (something I’ve done myself once or twice). A friend once suggested an intriguing alternative: perhaps some people, employing magical thinking, enter my email address at website.com with the hopes that it will somehow become theirs in the process. In any case, it seems especially common in Indonesia, with Malaysia, the Philippines and India coming in behind. I assume those are simply places where Azriel is a common given name.

Now, in a sane world, website.com would immediately send me an email with a confirmation link, asking me to verify that I really did just attempt to sign up for their service. The link would expire within 24 hours, at which point the account would be permanently removed and no further email would be sent to me. And some sites even get this right: for example, kudos to crunchyroll (“the official source to watch your favorite Japanese shows”) for sending me a single verification email, and nothing thereafter when I didn’t respond. Even fling.com (“Worlds Best Personals for Adults”) stopped emailing me right away (sorry, ladies). Google gets this partly right. When a new user attempts to add my address as a “recovery address”, I get an opt-out message that says (usually in Indonesian) that the connection has been made, but offering me a link to click to disavow that connection. That would be fine if it happened once every six months, but at present I average more than one a week. Google, could I please opt in, not out?

Unfortunately, many sites get this completely wrong, and immediately begin inundating me with information intended for others. It’s particularly heinous when the information violates the intended recipient’s privacy. I have received payment notices and class schedules for a student at an Indian vocational school, insurance premium information from AXA and Liberty mutual, and phone bills (including numbers and personal information) from Globe Telecom. When AMEX sent me a customer’s home address (in a message that told me how much they valued my privacy!) I thought about sending that person a postcard, but spending money smells like defeat.

At this point, the Game begins: can I stop the company from emailing me? Often, because the account connects to my address, I can simply request a password reset. Then, having taken over the account, I delete it or, because that’s often impossible, change the email address (protip: use “nobody@example.com”) and login password. Sometimes it’s not that easy. Some websites demand additional information like a PIN, date of birth, or credit card digits for password reset (in one case, one particularly lazy afternoon I was able to guess the person’s date of birth after only a few hundred tries). Some authenticate via a third party (Twitter, Facebook, Google). Some have geographic restrictions that prevent me from logging in at all, even though they’re emailing me.

Round two involves contacting customer service. This can be surprisingly challenging. Companies seem loath to supply email addresses for direct contact. Many online service forms assume you’re a customer, and demand account information or that you be logged in. The real irony, of course, is that I’m not a customer. This company’s crappy software has turned the incompetence of one of their customers into my problem, which is no way to make a positive impression out in the world.

Round three consists of airing the company’s dirty laundry by tweeting at them. Twitter is absurdly effective as a means of obtaining customer service. It seems to operate as an end run around normal channels, compounded by the company’s need to look good in public. Plus, it allows me to poke fun at Kafkaesque customer service, which is fair compensation for forcing me to wander a company’s customer service labyrinth. My favourite example is last year’s encounter with Globe Telecom in the Philippines. I told them I was receiving someone’s private phone bills, and they suggested I phone the customer and ask them to fix their address online. Aren’t they the phone company?

Round four is the final challenge: attempt to beat the company at their own game. Last month, I won a fourth-round decision against HDFC Bank in India. A student in New Zealand registered a new bank card using my email address, and I immediately started receiving messages about every one of their purchases, usually things like coffee at the AUT (Aukland University of Technology) Counter Cafe. I couldn’t take over the online account, so I complained to the company on Twitter, making the simple request that they remove my email address from their records. They promised several times to look into it, while I continued to receive a steady stream of purchase information. Finally, 19 days later (!), they sent a message saying that they had deleted my email address. In the meantime, this Azriel-wannabe’s purchases revealed their identity enough that I was able to track them down online and email them directly. The day before the bank contacted me, the cardholder responded to my email; the narrowness of my victory made it all the sweeter.

I suppose there ought to be some takeaways from this long rant:

- If you offer a web-based service where customers can create accounts using an email address, always send a verification message with a link to click on. Do this even if you’re using a third-party service for authentication, since that service may not have verified a user’s email address.

- Don’t send any further emails until the account has been verified.

- Barring the above, make it easier for non-customers to obtain customer service. If your “delete my account” page asks for a reason, include “I didn’t create this account in the first place” as a reason.

Oh, and if anyone knows Azriel Magallanes Figueroa of San Enrique in the Philippines, please tell him he owes Globe Telecom PHP 3,561.48 by Monday. Thanks.

Leave a Reply